5 Supermarket Secrets You Probably Didn't Know About

Check out the facts.

Supermarkets: they’re everywhere, and unless you’re some sort of robot that doesn’t need to eat, you can’t really avoid shopping there. The reality is that human beings need food and — let’s be real — most of us aren’t growing our own wheat or milking our own cows, so the supermarket remains the preeminent point of interaction between us, the consumer, and the vast, faceless food industry. While the source of our foods seems increasingly distant nowadays, the dominance of supermarkets in delivering food products to customers has not always been the case.

The process of obtaining groceries was once very different than it is today. In the late nineteenth century, the Atlantic and Pacific Tea Company (better known today as A&P), discovered that there was significant profit to be made in creating a one-stop shop for consumers to purchase food. Enter the grocery store. But in this system, customers had to request products from a clerk, who then retrieved the goods from the back of the store. Californians Albert and Hugh Gerrard decided that this process could be streamlined by allowing customers to retrieve their own products, and created the first self-serve grocery store. Interestingly, the Gerrards’ grocery store was organized alphabetically (imagine buying your bananas, beef, and bread all in the same section?!).

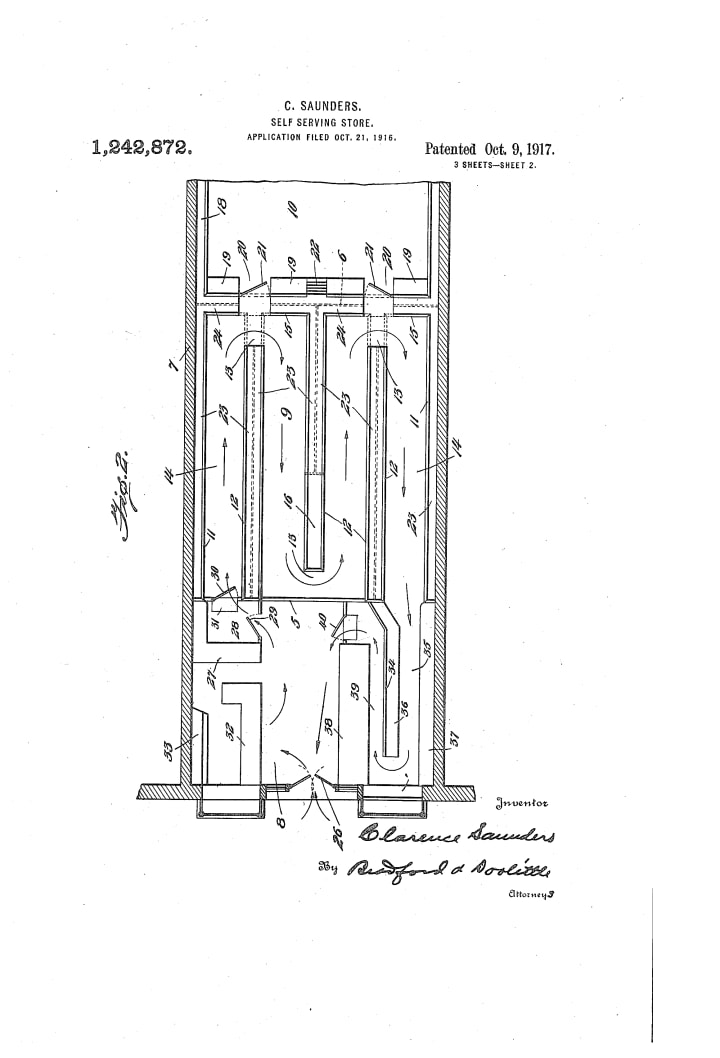

It was Clarence Saunders, in 1916, who truly revolutionized the supermarket as we now know it. His Memphis, Tennessee store, Piggly Wiggly, offered a whole new structure: a turnstile, followed by a ‘maze’ of groceries, leading back to the cash register where the customer then pays and leaves. The supermarket was entirely self-serve, and encouraged customers to load as much as possible into their carts before checking out. Saunders even patented his idea, and it quickly caught on, in a large chain of Piggly Wiggly stores, and a number of other supermarkets that adopted Saunder’s idea. Today, it would be hard to imagine a supermarket without this structure. It is in large part due to Saunder’s innovative store design that supermarkets have become the massive conglomerations that they are today. But as such, they do a lot that the average customer has no idea about.

Clarence Saunder's Patent for a Self-Serving Supermarket, 1917.

Source: US Patent Office.

Secret #2: They track your every move.

It started with the Universal Product Code (UPC), better known as the barcode, a 12-digit code represented with black-and-white lines read by lasers, first used in the U.S. in the 1970s. A replacement for the traditional price sticker, UPCs allowed supermarkets to find out precisely what was being purchased for inventory purposes. In recent years, this process has been taken many, many steps further; supermarkets are now doing a substantial amount of surveillance on their customers through various methods. The first is loyalty cards, varying across different stores, but all linking your name, address, and other personal information with your shopping habits. For supermarkets, this information is a goldmine; the data gained from these cards not only useful for supermarket inventory, but is used for targeted marketing. For instance, the U.K.’s Tesco supermarket chain sends its customers flyers tailored exactly to their shopping habits, based on information obtained from their loyalty card program. On the surface, customers may be pleased to receive marketing material aimed at exactly what they like to purchase. However, in a more startling scenario, supermarket loyalty cards led to the wrongful accusal of a customer, whose account was linked to particular brand of fire-starters, in an arson investigation.

The second way that supermarkets are tracking customers is through the replacement of UPC barcodes with RFID Electronic Product Codes (EPCs). These codes feature not only a number for manufacturer and product ID as with UPCs, but also a small passive radio. This radio can provide information on what consumers actually buy, and also on what they don’t. Through radio transmission, they are able to determine products that were once in the customer’s cart, but were eventually removed. RFID is seemingly the future of supermarket surveillance. There has been proposed use of embedded RFID technology in shopping carts as a means of tracking the route taken by customers to navigate the supermarket. While this specific technological monitoring hasn’t yet been brought to fruition, the ‘Big Brother’-esque surveilling already in place is very unsettling to many. RFID and personal information such as that collected for loyalty cards have not yet been linked, so supermarkets cannot yet tell when Jane Doe places Products A, B, and C in her cart; such a scenario of data collection would create a serious ethical dilemma. Even though such a dilemma does not currently exist, many customers still find this process of information gathering and surveillance to be invasive.

Take, for example, London’s Piccadilly Circus, whose famous billboard was recently renovated, and reopened last month. The new billboard features technology with embedded cameras that track the age, gender, and mood of pedestrians, as well as make and model of cars passing through the vicinity, and plays advertisements on the billboard according to this data. Further data is gained from free Wi-Fi offered in the area. While Landsec, the company responsible for the billboard and Wi-Fi services, insists that the data from this project has been either recorded or stored, the nature of data collection in today’s day and age is that it may be eventually be sold. This has raised controversy surrounding what has been dubbed the "Big Brother billboard," and is something that logically extends into market research and information gathering in the supermarket industry. Surveillance is already happening, but in the years to come, it is inevitably going to become even more rampant as technological advances continue.

The 'Big Brother Billboard' at London's Piccadilly Circus.

Source: BBC.

Secret #3: They play with your subconscious.

There is a growing field of academics — often whose research is utilized by grocery stores — who study the use of music and colours in supermarkets as a means of influencing shopping habits and increasing spending. In 1982, Ronald E. Millman conducted a study called Using Background Music to Affect the Behavior of Supermarket Shoppers to examine the impacts of music in supermarkets. He focused specifically on the tempo and familiarity of music, and found that, for strategic purposes, supermarkets should be using slow, bland, unfamiliar music. Slower music means that customers shop at a more leisurely rate, spending more time in the store, thus leading to higher sales. Millman also found that customers are typically unlikely to recall the music that they hear in supermarkets, therefore familiarity does not matter, hence the term "supermarket music."

The use of colours in supermarkets has also been examined to determine how certain colours can draw customers to displays of products, elicit certain feelings, and ultimately impact purchase rates. It is for this reason that "sale" signs are always red or orange; these colours have a tendency to "alert" customers and draw them to those products. Says research design consultant Linda Cahan, “people buy more when there is red.” Furthermore, stores have often tinkered with the use of cool colours — blue, green, yellow — to create a more calm and serene setting, further perpetuating Millman’s findings that customers are more likely to shop longer and spend more in a slow, leisurely environment. Things we see as customers as merely sights and sounds are, in reality, being deeply analyzed by academics and the higher-ups of the supermarket industry for the sole purpose of getting customers to spend more money.

Secret #4: They disconnect you from your food.

Let’s be honest: most of us have no idea where the vast majority of our food comes from. And why should we? The food industry has taken steps to disconnect consumers from those producing their food. Indeed, in the early days of Clarence Saunder’s Piggly Wiggly supermarket, employees were not even supposed to be present in the store to assist customers with product information (although, thankfully, this has changed). Author Raj Patel notes that “the only possible point of contact between the person eating the food and the person who grew it became the label on the tin” or packaging. The sweeping effects of globalization, increasing rapidly especially in recent decades, means that foods come from all across the planet to end up at your local supermarket.

It is true that the label is often the only connection the customer has to the food’s origins. This means that consumers must take the label’s information to be fact, and must trust that the food is indeed from where it says it’s from, that it is organic, gluten-free, non-genetically modified, etc. As a result, customers never know the intricacies of the lives of those who toiled to produce the food that we eat. Truthfully, the lives of those growing food, often in the developing world, are not great. Supermarkets and food conglomerates in the developed world, concerned solely with turning a profit, often make their money at the expense of their growers, who are paid next to nothing for the foods they produce. The result is massive debt and even higher suicide rates among farmers at the ground-level of the global food system. As passive consumers, this is something that most of us are never even aware of. Yet, by failing to educate ourselves on the tragic nature of the food system and accordingly make informed decisions, we are also willing participants in this horrific process.

Okay, but who farmed those bananas in Ecuador?

Source: Don't Waste the Crumbs

Secret #5: They’re preying on the less affluent.

Though no supermarket conglomerate would ever admit it, the statistics exist to support claims that supermarket chains are picking on the less affluent. Supermarket chains are most eager to place their stores in areas that can afford to buy their products, and buy lots of them. Typically, these locations are contingent upon access by car. By placing supermarkets in such locations, supermarkets create "food deserts" elsewhere, areas where there is no access to grocery items within a reasonable walking distance. This is not a big issue if you own a car, but if you do not, and rely on public transport or walking, this poses a major problem. Sadly, the issue of food deserts disproportionately affects people of colour; Raj Patel notes that “supermarkets have been increasingly reluctant to enter neighbourhoods of people of colour,” where customers are statistically less affluent. And the disadvantages do not stop there. When supermarkets do decide to enter neighbourhoods in such markets, they typically engage in a process called "supermarket redlining." They sell less produce and more processed foods than their counterparts at supermarkets in more affluent neighbourhoods. This, in turn, leads to increased rates of obesity among those who cannot access or afford nutritious foods. Even worse still, according to a 1991 New York City Consumer Affairs study reported in the Economist, the lower-income neighbourhoods were paying 8.8 percent more for their groceries, simply because supermarkets held a monopoly in such neighbourhoods and abused this role.

All this can leave you with major trust issues as you contemplate your next trip to the supermarket. Yet, most of what supermarkets do is perfectly legal. Barring some discrimination cases that have been heard in the U.S. regarding ‘redlining,’ supermarket companies generally cross their T’s and dot their I’s with a number of legalities surrounding their stores. For example, most consumers don’t realize that when they sign up for loyalty cards, they grant the store consent to monitor their purchases, visa the fine print that no one ever reads.

No reason to fear, however; if any of these supermarket secrets come as a surprise to you, and you take issues with the internal structures of supermarkets and the food industry, there is much you can do to mitigate these factors. First, you can grow your own food. Realistically, you’re likely not going to produce meat or dairy products, but fruits a vegetables are a realistic option. With a little TLC and a green thumb, you can avoid the often abusive middleman and know exactly where your food is coming from. As well, you can buy local, from places like farmers markets and small-scale locally-owned grocery stores, or the lesser-known alternative, Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) systems. CSAs offer delivery of freshly-grown, in-season food, right to your door, eliminating the issue of food deserts and connecting farmers and food producers to consumers. CSAs are also environmentally friendly, as they cut down the "food miles" necessary to take products from field to fork. Unlike supermarket conglomerates, these local options not concerned with playing music or using colours that will make you buy more. They simply want to support themselves and their families.

Finally, you can inform yourself; it is pivotal to not be a passive consumer, but rather to read and educate yourself about how supermarkets and the food system as a whole operate. Not matter who you are, the global food system impacts you in some way, shape, or form; as humans needing to eat, this is simply unavoidable. But by learning about the way this system functions, you — as a consumer — can make informed decisions about the food that sustains you. Raj Patel’s Stuffed and Starved and Tony Weis’s The Global Food Economy are two excellent books on these topics, along with numerous academic and internet articles on the subject. The behind-the-scenes actions of supermarkets can be scary — and most people don’t ever even know about it — but rest assured, by being aware of the nature of supermarkets, and educating yourself about their intricacies, you can ensure you’re not left in the dark.

About the Creator

Logan Carmichael

Political Science grad. Aspiring diplomat.

There's hidden politics behind the food you eat, and I'm here to tell you about it.

Comments

There are no comments for this story

Be the first to respond and start the conversation.